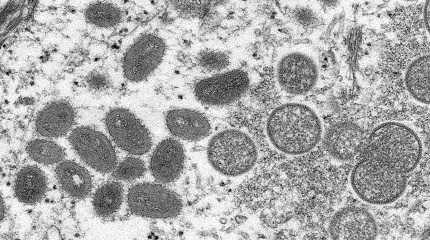

LONDON, Aug 30 (Reuters) - It is possible to eliminate the monkeypox outbreak in Europe, World Health Organization officials said on Tuesday, highlighting evidence that case counts are slowing in a handful of countries.

There are encouraging signs of a sustained week-on-week decline in the onset of cases in many European countries, including France, Germany, Portugal, Spain and Britain, as well as a slowdown in some parts of the United States, despite scarce vaccine supplies.

"We believe we can eliminate sustained human-to-human transmission of monkeypox in the (European) region," said WHO Regional Director for Europe Hans Kluge. "To move towards elimination...we need to urgently step up our efforts."

The rollout of Bavarian Nordic's (BAVA.CO) monkeypox vaccine has been affected by limited supply of the shot, which is also approved to prevent smallpox, although regulators are taking steps to stretch out existing stocks.

U.S., European Union and British regulators have backed changing the way the vaccine is administered by injecting a smaller amount of the shot intradermally, which increases by fivefold the doses that can be used from one vial.

In addition to the vaccine supply crunch, given the time it takes to deploy the vaccine and for it to take effect, the significant factors behind the slowdown appear to be earlier detection, which leads to patients isolating themselves sooner, and behavioural changes, Catherine Smallwood, senior emergency officer and monkeypox incident manager at WHO/Europe said in a press briefing.

"We do have some pretty good anecdotal evidence that people - particularly men who have sex with men who are in particular risk groups - are much more informed about the disease."

More than 47,600 confirmed cases in 90 countries where monkeypox is not endemic have been reported since early May. The WHO has declared the outbreak a global health emergency.

COVID, POLIO

Meanwhile, cases of COVID-19 and other respitory viruses are also expected to see an uptick this autumn and winter, as is typically the case in the cooler months, WHO officials said.

The preventative measures that kept seasonal flu at bay in 2021 and 2020, for instance, are no longer in place - so it may not be a typical flu season this year, Smallwood said.

Separately, polio, a deadly disease that used to paralyze tens of thousands of children every year, is spreading in London, New York and Jerusalem for the first time in decades, spurring catch-up vaccination campaigns.

The cases appear to be linked to so-called vaccine-derived polio, which rarely stems from the use of an oral polio vaccine containing weakened live virus.

After children are vaccinated, they shed virus in their faeces for a few weeks. In under-vaccinated communities, this can lead to a spread of the disease, which may mutate back to a harmful version of the virus.

While countries like Britain and the United States no longer use this live vaccine, others do - particularly to stop outbreaks - which allows for polio to spread globally.

The evidence suggests the polio virus detected in all three locations appears to be genetically linked, said WHO/Europe's vaccination expert, Siddhartha Datta.

But what remains to be investigated is whether there are links around the cases, he said.