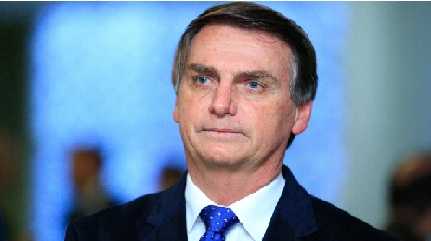

RIO DE JANEIRO (AP) — Jair Bolsonaro outperformed the polls in the first round of Brazil’s presidential election, forcing a runoff while proving that the far-right wave he rode to the presidency remains a force and giving the world yet another example of surveys missing the mark.

The most-trusted opinion polls had indicated leftist former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was far out front, and potentially even clinching a first-round victory on Sunday. One had given da Silva a 14 percentage point lead. But Bolsonaro came within just five points of da Silva, who he will face in a high-stakes runoff on Oct. 30.

Still, da Silva came close to an outright majority with 48.4% of the vote to Bolsonaro’s 43.2%, according to Brazil’s electoral authority. Nine other candidates split the rest.

“This is a big defeat for the democratic center that saw its voters migrate to Bolsonaro,” said Arilton Freres, director of Curitiba-based Instituto Opinião. “Lula starts ahead, but it won’t be easy for him.”

The vote was virtually free from the political violence that many had feared. Alexandre de Moraes, the Supreme Court justice who also leads the electoral authority, congratulated Brazil for the “safe, calm, harmonious and peaceful” election that demonstrated its democratic maturity.

Yet tensions remain high, as are the stakes. The election will determine whether the country returns a leftist to the helm of the world’s fourth-largest democracy or keeps Bolsonaro in office for another term.

The past four years have been marked by his incendiary speech, testing of democratic institutions, widely criticized handling of the COVID-19 pandemic and the worst deforestation of the Amazon rainforest in 15 years. But he has built a devoted base by defending conservative values and presenting himself as protecting the nation from leftist policies that he says infringe on personal liberties and produce economic turmoil.

“I understand there is a desire from the population for change, but some changes can be for the worse,” Bolsonaro told reporters after the results were released. Bolsonaro has repeatedly claimed — without citing evidence — that the nation’s electronic voting machines are vulnerable to fraud, but didn’t challenge the result.

Da Silva is credited with building an extensive social welfare program during his 2003-2010 tenure that helped lift tens of millions into the middle class and saw exports surge amid the global commodities boom. He is also remembered for his party’s involvement in corruption scandals and his own convictions, which were later annulled by the Supreme Court that ruled the judge had been biased. That freed him from imprisonment and cleared the way for his presidential run.

Many voters apparently veered to Bolsonaro after earlier favoring candidates with little chance of victory, according to analysts. Those also-rans did worse than anticipated.

“People who were originally voting for Simone Tebet or Ciro Gomes (the third and fourth place finishers) decided at the last minute to vote for Bolsonaro,” said Nara Pavão, who teaches political science at the Federal University of Pernambuco.

The result “leaves a bitter taste for the left, if we consider what the polls were showing.” said Rafael Cortez, who oversees political risk at consultancy Tendencias Consultoria.

Bolsonaro and allies have repeatedly cast doubt on the reliability of pollsters like Datafolha, and pointed instead great turnouts at his street rallies.

“Many people were carried away by the lies propagated by the research institutes,” Bolsonaro wrote Monday on his Twitter profile. “All their predictions were wrong and they are already the biggest losers of this election. We beat that lie and now we’re going to win the election!”

The difference between Bolsonaro and da Silva in the first round amounted to 6.1 million votes. Tebet and Gomes together earned 8.5 million votes, and more than 30 million people abstained.

Although Tebet has hinted she could urge her backers to support da Silva, neither she or Gomes have made clear statements yet as to who they will back on Oct. 30.

Speaking after the results, da Silva said he was excited for another few weeks of campaigning and the opportunity to go face-to-face with Bolsonaro and “make comparisons between the Brazil he built with the Brazil we built during our administrations.”

“I always thought that we were going to win these elections. And I tell you that we are going to win this election. This, for us, is just an extension,” da Silva said.

The right’s positive night extended to races for governorships and congressional seats, especially candidates with Bolsonaro’s blessing. His former infrastructure minister won the race to govern Sao Paulo. The governor of Rio de Janeiro, an ally, vanquished his opponent to win reelection outright.

Sergio Moro, the former judge who temporarily jailed da Silva and was Bolsonaro former justice minister, defied polls to win a Senate seat.

And Bolsonaro’s Liberal Party will surpass da Silva’s Workers’ Party to become the biggest in the Senate and the Lower House.

Among its victors were Bolsonaro’s former health minister, a general who oversaw the troubled management of the pandemic, and his former environment minister, who resigned amid an investigation into whether he had aided the export of illegally cut timber in the Amazon.

“The far-right has shown great resilience in the presidential and in the state races,” said Carlos Melo, a political science professor at Insper University in Sao Paulo.

Bolsonaro told reporters that his party’s showing in Congress could bring fresh endorsements ahead of the Oct. 30 vote, as other parties strike alliances in exchange for support in the runoff.

“Brazil is much more polarized than many people thought, and governing will be difficult for whomever wins,” said Brian Winter, vice president for policy at the Americas Society/Council of the Americas. “I think the next few weeks will put heavy strain on Brazil’s democracy as these two men fight it out. Expect an ugly race that will leave scars.”